What can we do?

Seven ways to help shine a light on forgotten crises

With so many different types of disasters and conflicts repeatedly ignored by the media year after year, the question remains: what can or should be done? While the reasons for a crisis to be forgotten may share commonalities, the solutions can be many and varied. Anything from simple actions to creative attempts can make a difference. But doing nothing is not an option. Here are seven important actions that are crucial to shine a light on millions of people and their suffering.

For governments and policy-makers

1. Consider reporting as a form of aid:

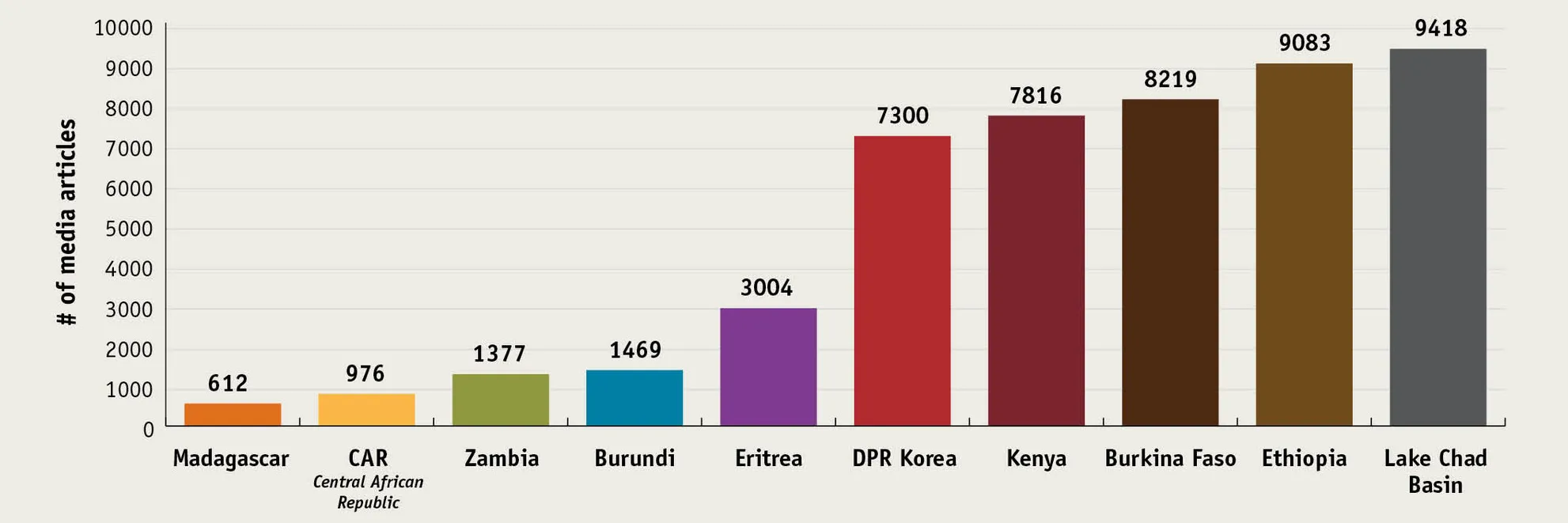

Reporting on crises surely cannot compete with life-saving assistance in the form of food, clean water or medical aid. However, crises that are neglected are also often the most underfunded and protracted. A quick analysis shows a strong correlation between the amount of media coverage and funding received: 3 of the 10 most under-reported crises in this report also appear in the UN’s list of most underfunded emergencies in 2019.78 With close links between public awareness and funding, it needs to be acknowledged that generating attention is a form of aid in itself. As such, humanitarian funding should include budget lines to raise public awareness, particularly in low-profile countries. This can be used to encourage affected countries to increase their local news coverage, to offer press visits to emergency- affected areas, or to provide logistical support and training for journalists. At the same time, it is crucial that press freedom constitutes a condition for receiving aid. Affected countries have a responsibility to support unrestricted coverage and unhindered media access in order to improve humanitarian conditions. Press freedom is essential to shine a light on issues that would otherwise be forgotten.

2. Money is not enough:

In order to reach an increasingly younger, active and diverse population, it is crucial

to use voices that can reach wide audiences. In today’s world, policy-makers more than ever are required to engage and inform the public. Young people are increasingly concerned about the interconnected climate and humanitarian crises occurring in their backyard. They would like to be educated through in-depth, trustworthy information with on-the-ground stories in real time, from real people. In a digital landscape built on attention and speed, there are many opportunities for governments and policy- makers to demonstrate their commitment and help drive media attention to crises, starting from a simple tweet to participating in a campaign on forgotten crises.

For the media

3. Reporting on the under-reported:

Representation matters and reporting on the misery and adversity of marginalised people79 is extremely important to ensure that their voices are heard and concerns addressed. When covering sensitive or complex issues, media outlets must ensure that linkages are explained – for instance, recognising the diverse forms of gender-based violence including early marriage and intimate partner violence, or the ties between human-made climate change and its consequences on stressors such as forced displacement, conflict, health or gender inequality. While the number of people in need is likely to rise in the coming years, their suffering cannot be ranked, regardless of the extent of a disaster. Focusing only on the number of deaths can shift attention away from underlying challenges and overlook people who will urgently need help. Media attention on under-reported issues helps to move the mainstream narrative from numbers to impact and from outcomes to root causes. Examples of change include committing to devote a certain percentage of world coverage to humanitarian crises that do not receive sufficient attention; sending one reporter to one forgotten crisis per year; or doing one round-table event about a forgotten crisis advertised through your platform.

4. Stories of hope:

More and more research points to the fact that fear and pessimism trigger conservative and suspicious views, while hope and optimism tend to generate more liberal views. The project “Hope not Hate” states: “Where people are more likely to feel in control of their own lives, they are more likely to show resistance to hostile narratives, and are more likely to share a positive vision of diversity and multiculturalism.”80 “Hidden Tribes”, a 2018 report from “More in Common,” 81 insists that the media landscape accentuates the conflicts but downplays the solidarity in our society. It advises us to find common ground to counteract the divisions magnified on our screens with stories of human contact and respectful engagement that “spotlight the extraordinary ways in which [people] in local communities build bridges and not walls, every day”. In the midst of crises and suffering, it can be difficult to find positive angles. But when they are found, they can be a powerful force to combat populist fear framing and dehumanization and instead trigger empowerment and solidarity.

For aid agencies

5. Focus on the people and solutions:

Dwindling news budgets, plummeting advertising revenue and downsizing of foreign correspondent networks have left a void in crisis coverage. This is increasingly filled by aid agencies who provide news content or organise press visits. While aid agencies can and should play their part in reporting on neglected crises and highlighting the voices of people affected, it is important to recognise the need for localised angles when pitching stories not necessarily in line with their agendas. Humanitarian organisations have a duty to promote the role of local and national actors and acknowledge the work that they carry out. Including them as spokespeople when security considerations permit is crucial. Issues of trust, professionalism, norms and ethics play a major role on both sides. While aid agencies are often restricted in political messaging for reasons of impartiality or relying on local administrations to provide aid, the media has an obligation to report based on transparency, neutrality and accuracy. It is crucial to understand each other’s limits, risks and goals so that partnerships can truly address the local needs of those suffering.

For the public

6. Lend your voice to the voiceless:

Know that your voice can and does make a difference, even if your newspapers, TV and phone screens are devoid of ‘good news’. Volunteering your energy, money and time can feel like a drop in the ocean, especially when you take action on some of the world’s most forgotten crises. But every supporter action can and does make a difference. We have witnessed how one Swedish teenager’s climate change protest grew into a global movement of millions. Across Africa and other parts of the globe, more than 6.7 million women are turning empowerment into financial independence and better lives through CARE’s village savings groups.82 With the rise of citizen journalism and people taking issues to the streets around the world, there is no doubt that every voice matters and can start or strengthen a movement towards change.

For businesses

7. Help responsibly

Recognize corporate social responsibility not primarily as a PR or image boost, but as a duty towards the communities affected by conflict and natural disaster – many of which are caused by extractive and other industries. Consider carefully the investments you are making in humanitarian settings and work towards a triple bottom line of people, planet and profit. Ensure that any investments made in humanitarian settings are done for the long-term benefit of local communities. While leveraging strengths and assets, keep in mind that the most urgent needs of people in need are typically food, clean drinking water, emergency shelter or medical care. In most cases, cash contributions are much more effective than in-kind donations, allowing needs to be covered and ensuring donations will feed into the existing humanitarian response. Also, providing flexible emergency funding to NGOs can help them respond better to forgotten crises. Moreover, address and reduce your contributions to underlying stressors such as human-made climate change.

About CARE International

Founded in 1945, CARE International works around the globe to save lives, defeat poverty and achieve social justice. We put women and girls in the centre because we know that we cannot overcome poverty until all people have equal rights and opportunities.

CARE International works in 100 countries to assist more than 68 million people to improve basic health and education, fight hunger, increase access to clean water and sanitation, expand economic opportunity, confront climate change and recover from disasters. More than 70% of those helped are women.