What can we do?

Eight steps to help shine a light on forgotten crises

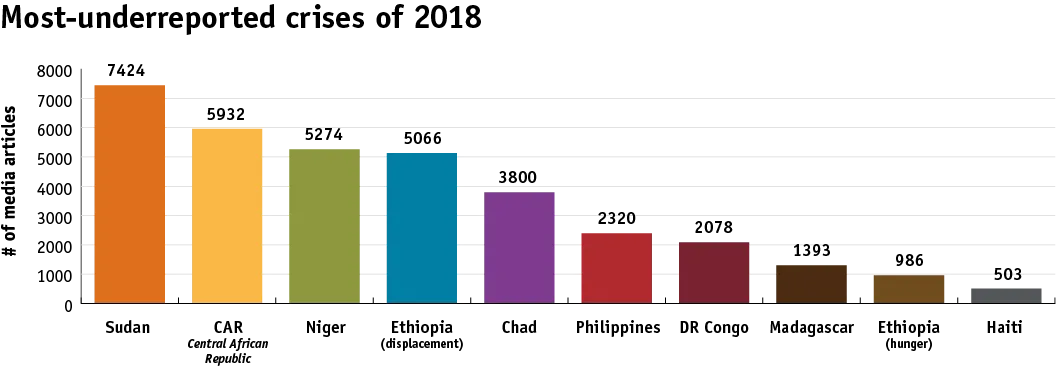

It has been a testing year for aid agencies. With so many different types of disasters and conflicts barely covered in the media the question remains: What can or should be done? The importance of media coverage and public awareness to help mobilise funds and increase pressure on decision-makers has been proven again and again. Still, the question on how to ensure better coverage of under-reported crises remains largely unaddressed. Some of the obstacles are well known. The media needs safe access to disaster-affected areas, requires funding for foreign reporting and needs to localise news coverage. But there is more to it. Here are eight important steps that are crucial now.

For Governments and Policy-Makers

1. No news is bad news

When human suffering is met with silence, the consequences are grave. Crises that are neglected are also often the most underfunded and protracted. Given that a number of crises in this report derive from food insecurity and the underlying risks of climate change, affected countries must push for media coverage to enable them to better meet the needs of the population. This not only means allowing reporters to cover stories with full access and safety, but also to proactively provide them with information on needs, achievements and gaps. In a digital landscape built on attention and visibility, this enables countries to demonstrate their commitment and helps media outlets tell the stories and call for much-needed action.

2. Media access as a condition of aid

Media access, visa issues and attacks on journalists continue to be one of the biggest obstacles for crisis reporting. According to the latest numbers of Reporters Without Borders, the media is facing an unprecedented wave of hostility, with 80 journalists killed in connection with their work, a further 348 imprisoned and 60 held hostage in 2018.[44] Press freedom is essential to shine a light on issues that would otherwise be forgotten. UN member states, donors and aid agencies must insist on media access as a condition of political support and aid to affected countries. This not only applies to international media but is of vital importance to local journalists. Much like local civil society organisations, they are on the frontline and need to be empowered to act when a crisis hits. The local media is instrumental as a credible source that understands the local context better than anyone else and continues reporting on emergencies long after international spotlights are gone. Only if countries continue to call out the denial of access and attacks on journalists will emergencies stay on, rather than off, the radar.

3. Chasing needs, not headlines

We know that crises that receive more attention also get more funding – but those in greatest need of humanitarian support are not necessarily those who make the news. With close links between media coverage, public awareness and funding, it needs to be acknowledged that generating attention is a form of aid. With dwindling news budgets leading to less investment in foreign coverage, humanitarian funding should include budget lines to raise public awareness, particularly in low-profile countries, so we can raise more funds to help. This could be used for aid agencies and other actors to offer press visits to emergency-affected areas, provide logistical support for freelance journalists, capture raw footage for news coverage or support training for journalists.

4. Speaking up on what matters

Politicians must use their voices too. Individual politicians can play a key role in driving media attention to crises that matter to their constituents, including diaspora groups, church groups and other civil society organisations working in trouble spots around the world. In some countries, parliamentary associations pride themselves on speaking up about issues that do not get adequate coverage. When they do, they can be a powerful force – not only to focus the government, but also to capture domestic media attention. Politicians can also work with civil society organisations to provide evidence and help formulate questions, speeches and motions to direct wider public attention towards the world’s forgotten crises.

For journalists

5. Putting women and children first

All people suffering from disasters and crises are uniquely vulnerable. But women and girls are doubly so. When extreme violence, hunger or climate affect them, they are the first to be trafficked for sex or child labour, the first to be exploited as tools of war and the first to lose their childhoods. Meanwhile, they are the last to eat, the last to be enrolled in school and, too often, the last to be valued.[45] Securing funding for the protection of women and children is difficult when other pressing needs, such as food or water, are often prioritised. Much-needed support for trauma counselling, reproductive health and addressing gender-based violence often remains underfunded. Reporting on the misery and adversity women and children endure is of major importance in order to ensure that their voices are heard and concerns addressed. When reporting on sensitive issues such as gender-based violence and abuse, media outlets must ensure proper consent practice and interview training for their reporters.

6. More space for aid

The emphasis on online outlets means that previous arguments of limited space in a newspaper or broadcast no longer applies. Journalism in the age of the open web has unlocked doors for reporting that transcends time and space, and offers limitless possibilities. News editors also need to challenge the assumption that audiences are uninterested in humanitarian news. According to a survey conducted by the University of East Anglia,[46] about 60% of people claimed to follow news about humanitarian disasters more than any other type of international news. While financial pressures can place strain on the ability of media outlets to send reporters abroad, it is important to approach the meaning behind conflict of interest guidelines and to critically question whether not telling an important story is the better alternative to accepting logistical support from donors or aid agencies to cover a crisis. Certainly, aid actors should not expect favourable coverage in return for assisting reporters to reach affected populations. Like the humanitarian principles that underpin aid work, journalism ethics need to be held up to the highest standards. In order to ensure the stories of those who suffer in silence are told, journalists and aid actors need to work together while respecting each other’s areas of responsibility.

For aid agencies

7. Telling a story together

Raising awareness and drawing attention to crises and disasters in the public is not only the job of the media. With citizen journalism on the rise and direct access to audiences, humanitarian organisations need to join forces to fill gaps. Aid agencies can and should play their part in reporting on neglected crises and highlighting the voices of people affected. Not only is it important to invest in trained communications and media specialists on the ground who can liaise with the public but to also think about innovative ways of reaching people, particularly given limited humanitarian funding. Hiring freelance communication experts shared between agencies or offering joint trainings to local journalists are some options.

For news consumers

8. Invest to grow

Interested in foreign aid and humanitarian news? Then support it. From subscribing to news outlets that best reflect personal interest, complimenting journalists on good reporting or letting reporters and editors know of the importance of humanitarian issues, there are plenty of ways for readers to support the media outlets that continue to report on humanitarian crises. Donors can also support journalism fellowship programmes, some of which encourage foreign reporting and independent journalism in developing or crisis countries.

About CARE International

Founded in 1945, CARE International works around the globe to save lives, defeat poverty and achieve social justice. We put women and girls in the centre because we know that we cannot overcome poverty until all people have equal rights and opportunities.

In 2018, CARE International worked in 68 countries to assist more than 46 million people to improve basic health and education, fight hunger, increase access to clean water and sanitation, expand economic opportunity, confront climate change and recover from disasters.

To learn more, visit www.care-international.org