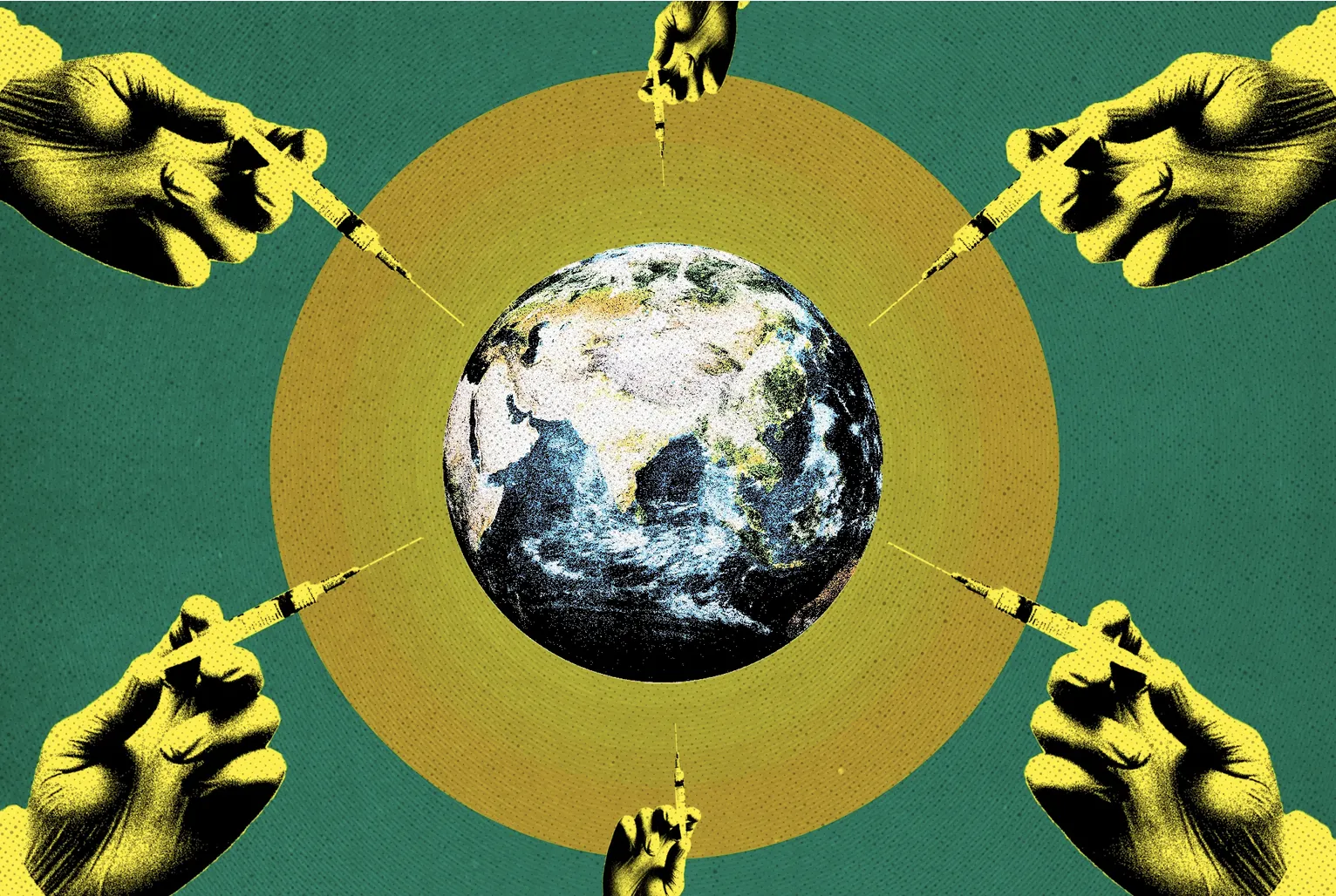

For the past year, public health experts have warned that leaving swaths of the world unvaccinated would be a recipe for incubating dangerous variants that could evade vaccines and prolong the fight against COVID-19. It’s still too early to tell whether omicron is the escape variant of virologists’ nightmares, but its sudden emergence has refocused attention on the lagging effort to vaccinate the globe.

Activists and even some federal health officials have criticized President Biden for slow-walking global vaccine donations, micromanaging distribution efforts through a small White House team (as first reported in Vanity Fair), and not forcing vaccine makers to share their technology with the developing world. But Biden has embraced the World Health Organization’s target of vaccinating 70% of the globe by next September, and the U.S. leads the world in its pledge to donate 1.2 billion doses, 275 million of which have already been shipped.

This summer, however, a disquieting reality began spreading within federal health agencies. A number of middle- and low-income countries, lacking robust public health systems, had difficulty absorbing and administering the donated vaccines—a failure of what experts call “vaccination readiness.”

To tackle this problem, in September, the National Security Council asked the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to prepare a detailed strategy to increase global vaccination readiness. A draft of the plan, which Vanity Fair has obtained, was designed by Boston Consulting Group contractors and had begun circulating within federal health agencies by October. It proposed covering operational costs in recipient countries, strengthening data systems, ensuring cold chains, and deploying rapid-response teams to identify bottlenecks. In short, it spelled out the need for a boots-on-the-ground effort similar to what has been required within the United States. “On-the-ground uptake challenges will become the most critical constraint within months,” the plan stated, adding, “We are seeing uptake challenges firsthand in countries receiving Pfizer and other bilateral donations.”